01.08.2026

Announcing MolSim-FE

Accurate physics-based affinity prediction at scale.

By The Rhizome Team

Today, we're introducing our module for accurate physics-based binding free energy prediction: MolSim-FE.

TL;DR

Ultra-large virtual libraries now enable screening across billions of synthesizable molecules, yet many programs still synthesize and assay only dozens to a few hundred compounds per target. Drug discovery remains a constrained search problem: the chemical space is vast, true binders are rare, and experimental bandwidth is the bottleneck. MolSim-FE is our novel free-energy module designed for these challenges: it combines rigorous statistical thermodynamics accuracy with adaptive lower-cost modes and active-learning-style prioritization to reduce wasted DMTA cycles and improve the quality of synthesis/testing decisions.

In a retrospective evaluation, we found that our fast ABFE coupled with active learning substantially improves triage performance: >10× enrichment relative to docking, while delivering triage-level signal at ~100× lower computational cost than applying higher-rigor ABFE uniformly at the same scale.

As GPU availability expands, the boundary between screening and rigorous physics continues to shift. With access to larger GPU fleets, free-energy evaluation can be applied to progressively larger candidate sets, moving more of the pipeline from heuristic scoring toward ABFE/RBFE-grade decision quality. MolSim-FE is designed to capitalize on this scaling opportunity.

Intro

Today, the arsenal of readily accessible computational chemistry techniques is broad, spanning from triage using docking (now reaching throughputs of 106 - 107 ligands per day on a standard GPU, see Yu et al., 2023, Raush et al., 2025), to foundation models such as Boltz-2 that can predict the binding pose and estimate affinity, and molecular dynamics simulations that assess the ligand's stability and interactions within the binding pocket over time.

These methods are relatively inexpensive and straightforward to deploy, and we integrate them into our pipelines wherever relevant (e.g., see the report on our generative model r1 & Boltz-2 integrated in an informed-generation loop). However, with ease of use and accessibility comes a challenge: these methods have limited accuracy[1]. This is a well-established consensus for docking [Moitessier et al., 2009, Warren et al., 2005, Cheng et al., 2012, Xue et al., 2025], as well as for non-rigorous molecular dynamics-based approaches such as trajectory-based end-point methods [Hou et al., 2012, Genheden & Ryde, 2015). And while Boltz-2 performs extremely well on well-characterized targets, it can be substantially less reliable for underexplored targets, induced fit & allosteric regimes or unusual binder chemistries [deepmirror.ai blog, rowansci.com blog, Lukauskis et al., 2025, Shen et al., 2025, Grieswelle et al., 2025].

Drug discovery programs typically synthesize and test dozens to a few hundred compounds per target per phase, making each selection critical [IMI-PREMIER deliverable; Novartis blog, Schrödinger article; Stanley et al., 2021]. At this scale, the accuracy of approximate methods like docking and end-point simulations is often insufficient because the selection of a few molecules from many requires minimal noise. This limitation is even more pronounced in lead optimization, where capturing affinity shifts resulting from small structural changes demands even higher precision.

Ultra-large libraries (1011 to 1012 compounds) are now accessible for experimental evaluation, having grown ~4 orders of magnitude over the last decade. Approximate methods can triage these libraries down to 104 to 105 candidates, but the true binders remain needles in this reduced haystack. To go further, selecting the final 100 to 1000 compounds for synthesis and in vitro testing requires more accurate methods than easily accessible computational chemistry workflows can support.

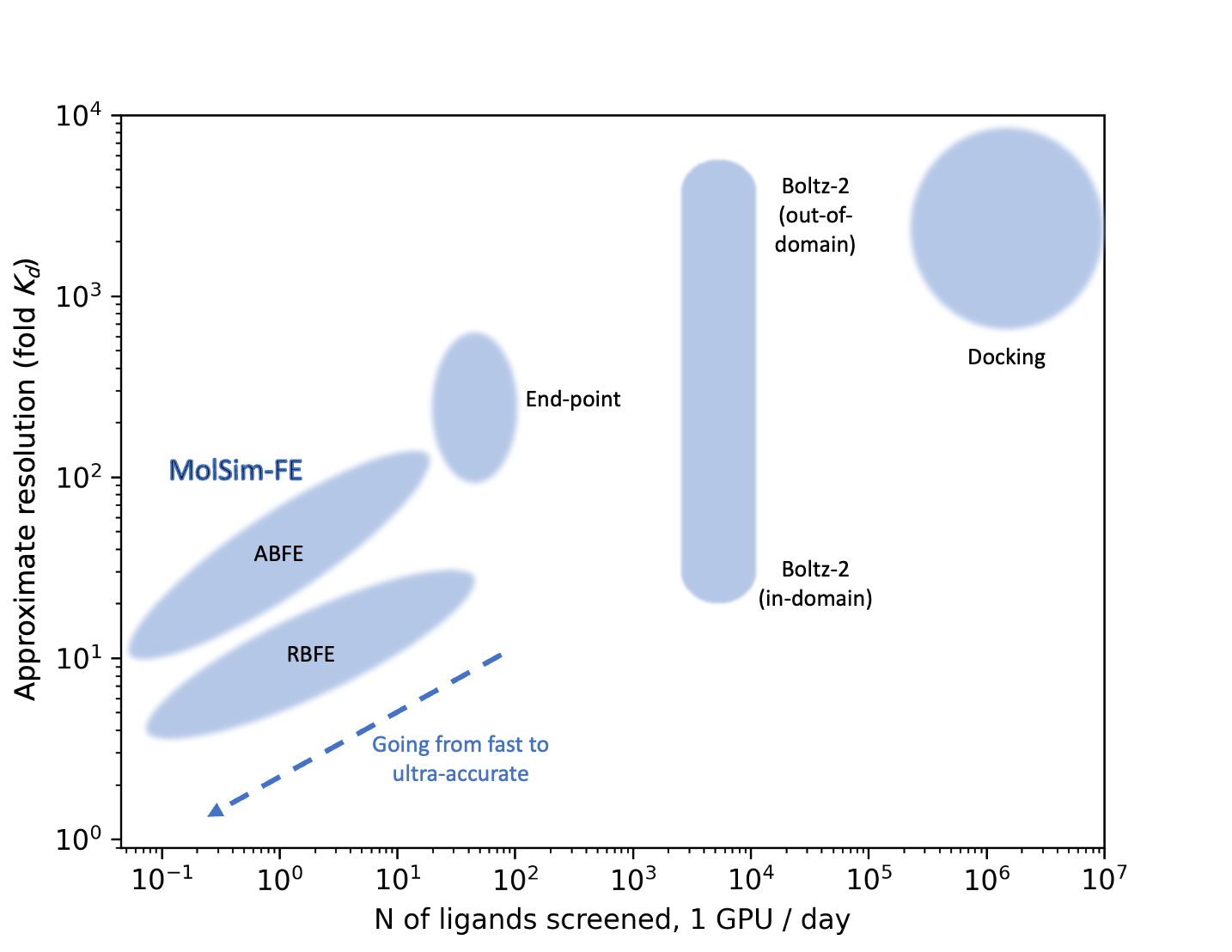

In summary, limited compound testing, lead optimization precision and ultra-large library rescoring are the core challenges. The solution lies in methods grounded in rigorous statistical thermodynamics: absolute and relative binding free energy calculations (ABFE/RBFE). ABFE predicts affinities across diverse chemotypes, while RBFE captures the small deltas critical for within-series (congeneric) comparisons. MolSim-FE excels at both. Figure 1 shows where ABFE/RBFE sit on the accuracy/throughput conceptual landscape relative to cheaper alternatives.

When it comes to binding affinity prediction, RBFE and ABFE are proven to provide superior accuracy to all computational chemistry alternatives [Fu et al., 2022, Bhati et al., 2024, Cournia et al., 2017, Bhati & Coveney, 2022]. These methods have experienced growing attention, with industrial benchmarks reflecting that momentum [Baumann et al., 2025, Wei & McCammon, 2024, Muegge & Hu, 2023].

At the same time, running these methods well remains challenging: reliable free-energy results depend on careful system setup, sampling strategy, and diagnostics, which is why robust deployment plans remain concentrated within specialist teams rather than being a push-button commodity.

MolSim-FE is our answer to that gap: We bring specialist-grade capability in-house and focus on making ABFE/RBFE practical at scale, enabling discovery programs to move beyond heuristic scoring when decisions become costly.

MolSim-FE is built on three innovation pillars: Quality, Versatility and Scale.

Quality

Our ABFE and RBFE modules are built around modern, state-of-the-art sampling approaches:

- Hamiltonian replica-exchange style to improve mixing and robustness in challenging regions of the alchemical path [Nawrocki et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2024].

- On-the-fly lambda window placement so the schedule reflects where the transformation is hard, departing from rigid lambda window templates [Clark et al., 2024; Midgley et al., 2025].

- Variable per-window sampling based on convergence behavior so that one avoids paying uniformly for lambda windows [Clark et al., 2024, Lee et al., 2025].

- Enhanced sampling around hydration/water placement because water states are often the main impediment to a smooth convergence [Jiang, 2019; Jiang, 2024].

Importantly, these high-quality sampling approaches enable a second pillar: Versatility.

Versatility

As demonstrated in Figure 1, ABFE and RBFE open a wide design space for navigating the throughput-resolution trade-off. MolSim-FE is built to make these different throughput-resolution regimes both usable and meaningful. With high-quality sampling guaranteed by our Quality Pillar, we can run ABFE and RBFE calculations in either fast or normal regimes, with or without an ensemble of independent replicates. We have also developed protocols for determining when each regime is most appropriate.

This flexibility allows us to span over two orders of magnitude in throughput while maintaining high levels of enrichment even in the fastest ABFE/RBFE implementations. MolSim-FE can therefore address both rapid triage and slower, ultra-accurate lead-optimization regimes.

To accelerate our methods even further, we have built a third innovation pillar focused on Scale.

Scale

As discussed previously, the goal of ultra-large screening is to enable accurate methods to rescore as many compounds as possible. However, even with our fast-mode ABFE/RBFE methods, screening is limited to a few dozen ligands per day per GPU. With 100 GPUs over 10 days, this approaches ~104 ligands, but reaching 105 would require another order of magnitude in throughput.

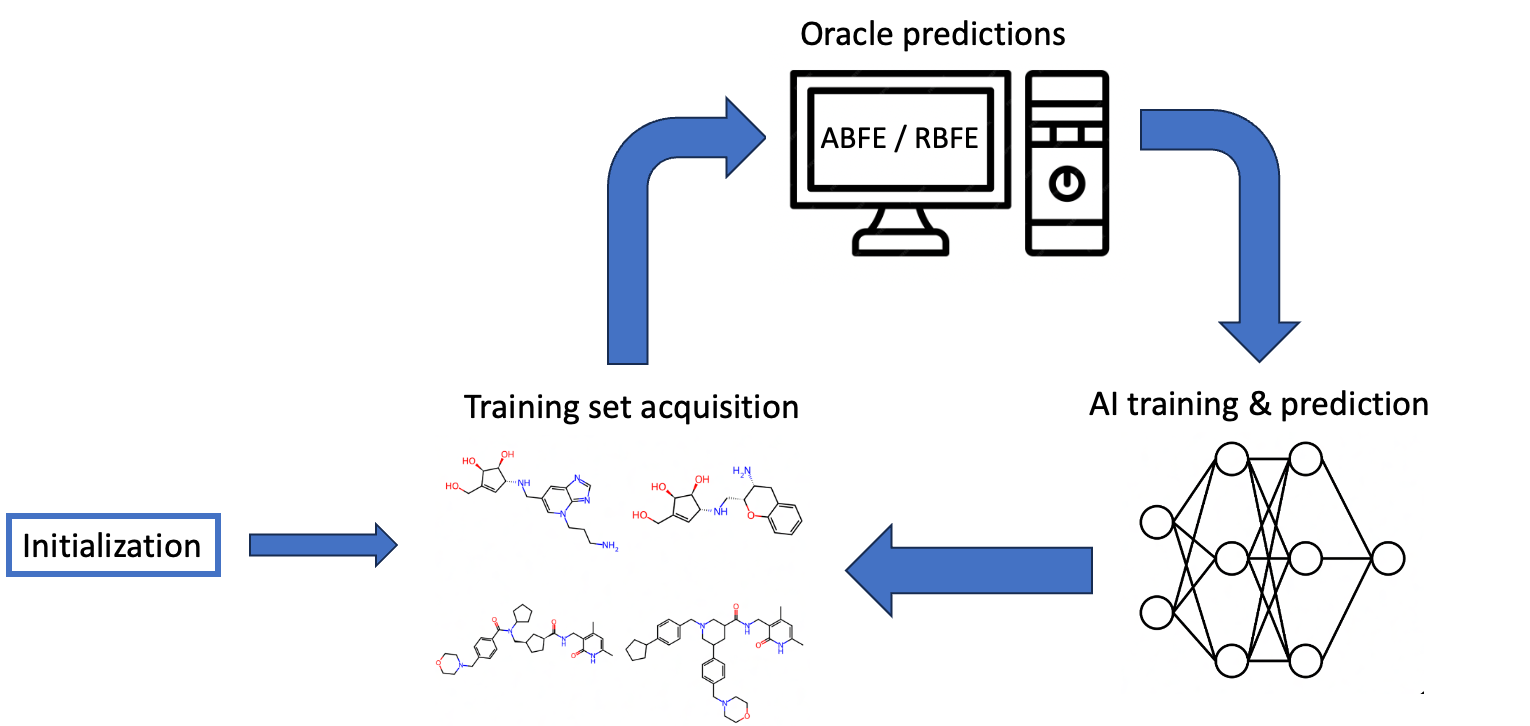

Active learning (AL) can bridge this gap. By strategically selecting compounds for expensive oracle (ABFE/RBFE) evaluation and training AI models on the resulting data, AL reduces the required compute by at least 10-fold. Figure 2 illustrates this approach and shows how MolSim-FE leverages this acceleration to achieve substantially higher throughput.

This expanded capacity unlocks a qualitative shift in what is possible. Rather than exhaustively testing variations of a single scaffold, researchers can now evaluate diverse clusters of ligands spanning multiple scaffolds simultaneously. This effectively compresses design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles by exploring more chemical space per iteration. This is where r1 becomes essential. Its generation of diverse candidates provides exactly the broad chemical exploration the MolSim-FE pipeline can now support.

Retrospective calibration: concrete numbers

Early on, we tested our fast ABFE + AL approach retrospectively on an oncology target within a partner workflow before applying it to a prospective campaign. We mixed 20 true binders with approximately 1,000 decoys and defined enrichment as the proportion of true binders ranked in the top 10% of the dataset.

Two key findings emerged from this exercise:

- >10× enrichment improvement for fast-mode ABFE + AL compared with plain docking as the triage signal.

- In the same setting, the AL-coupled fast-mode ABFE approach delivered this excellent triage-level signal while being ~100× faster than running a plain ABFE protocol across the same candidate set.

While retrospective results like these are useful for calibration, they do not constitute proof of generality. A single target, a single decoy set, and a single assay context can make almost any method appear to perform well. Retrospective ranking can degrade sharply when applied to new chemistries, new binding modes, or different assay formats. The only validation that ultimately matters is prospective: running the full information loop under real project constraints and measuring outcomes against standard methods along with synthesis and assay data. This is precisely why our current emphasis is on prospective application with collaborators rather than expanding retrospective benchmarking for its own sake. As these programs mature and comparisons become meaningful, we will share results that reflect real-world conditions rather than curated post hoc settings.

Scaling note: what more GPUs unlock for free energy calculations

Access to larger GPU fleets doesn't just make MolSim-FE run faster; it changes what's feasible, potentially enabling millions of molecules to be screened at rigorous physics-grade quality and fundamentally shifting early-stage drug discovery.

Our Vision: Agents + GenAI + MolSim-FE

Rhizome's direction is to couple three things into a single system:

- Generation: r1 discovers diverse, patent-eligible molecules that are primed for synthesis and optimization.

- Physics: MolSim-FE evaluates them using scaled, state-of-the-art, rigorous physics-based methods with the highest experimental accuracy.

- LLMs: Agents run the workflow end-to-end: setup, execution, monitoring, analysis, iteration.

With the launch of ADAMS: Agent-Driven Autonomous Molecular Simulations, one can see how multi-agent systems can already run basic drug discovery tasks when given tools. When equipped with more advanced drug discovery tools, such as r1 and MolSim-FE, these systems can support an autonomous loop for proposing, evaluating and analyzing high-quality drug candidates in a highly scalable way. Our bet is that the next step-change in discovery won't come from choosing either AI or physics. It will come from wiring them into a closed loop where generation is meaningful, evaluation is trustworthy, and iteration is autonomous. Foundation models will keep improving, and we'll use them where they help, but programs are still won on decisions that survive synthesis and assay. For that, physics-based evaluation remains the most defensible way to reason about binding, failure modes, and uncertainty across targets and chemistries.

[1] Which we broadly define here as the ability of the method to differentiate true binders from non-binders and accurately rank them.

[2] Overall, the accuracy and throughput of the accessible computational chemistry methods can be illustrated through an approximate fold resolution for protein-ligand dissociation constant (Kd) depending on the method family. For example, if the fold resolution is 100, it means that the method can differentiate between 100 µM and 1 µM binder (100 times difference in Kd), but not between 100 µM and 10 µM binder (only 10 times difference in Kd).

[3] Today a lot of power and talent is being allocated toward accelerating AI inference, we expect that Boltz-2 can accelerate in the future. However, our primary focus here is the level of accuracy for different use cases.

You can contact us at x@rhizome-research.com, fill out our form here or find us on LinkedIn for partnership opportunities.